Dogma in a Lab Coat

Welcome back to Taste of Truth Tuesdays.

My last episode “America Is Not Gilead, Calm Down”—was a spicy one, and apparently you all were here for it. We hit 859 downloads, so thank you for tuning in, sharing, and riding that wave with me.

But today, we’re shifting gears. There’s enough chaos in the current news cycle to make anyone dizzy, and honestly? We need a breather from the present. So instead of chasing headlines, we’re going back in time.

Today’s episode is about buried truths—forgotten cemeteries, white coats with dark legacies, and the disturbing roots of modern psychiatry. We’re peeling back the polished surface of “mental health” to expose the pseudoscientific, eugenics-laced ideology that helped shape it.

This one isn’t light, but it’s important. Because what we’re told is compassion often masks control. Because the scariest forms of control don’t always come with sirens and handcuffs sometimes, they wear stethoscopes and call it care.

Let’s dig in.

We like to believe science is self-correcting—that data drives discovery, that good ideas rise, and bad ones fall. But when it comes to mental health, modern society is still tethered to a deeply flawed framework—one that pathologizes human experience, medicalizes distress, and often does more harm than good.

Psychiatry has long promised progress, yet history tells a different story. From outdated treatments like bloodletting to today’s overprescription of SSRIs, we’ve traded one form of blind faith for another. These drugs—still experimental in many respects—carry serious risks, yet are handed out at staggering rates. And rather than healing root causes, they often reinforce a narrative of victimhood and chronic dysfunction.

The pharmaceutical industry now drives diagnosis rates, shaping public perception and clinical practice in ways that few understand. In this episode, we revisit the dangers of consensus-driven science—how it silences dissent and rewards conformity.

Because science, like religion or politics, can become dogma. Paradigms harden. Institutions protect their power. And the costs are human lives.

But beneath this entire structure lies a deeper, more uncomfortable question—one we rarely ask:

What does it mean to be a person?

Are we just bodies and brains—repairable, programmable, replaceable? Or is there something more?

Is consciousness a glitch of chemistry, or is it a window into the soul?

Modern psychiatry doesn’t just treat symptoms—it defines the boundaries of personhood. It tells us who counts, who’s disordered, who can be trusted with autonomy—and who can’t.

But what if those definitions are wrong?

We’ve talked before about the risks of unquestioned paradigms—how ideas become dogma, and dogma becomes control. In a past episode, How Dogma Limits Progress in Fitness, Nutrition, and Spirituality, we explored Rupert Sheldrake’s challenge to the dominant scientific worldview—his argument that science itself had become a belief system, closing itself off to dissent. TED removed that talk, calling it “pseudoscience.” But many saw it as an attempt to protect the status quo—the high priests of data and empiricism silencing heresy in the name of progress. We will revisit his work later on in our conversation.

We’ve also discussed how science, more than politics or religion, is often weaponized to control behavior, shape belief, and reinforce social hierarchies. And in a recent Taste Test Thursday episode, we dug into how the industrial food system was shaped not just by profit but by ideology—driven by a merger of science and faith.

To read more:

This framework—that science is never truly neutral—becomes especially chilling when you look at the history of psychiatry.

To begin this conversation, we’re going back—not to Freud or Prozac, but further. To the roots of American psychiatry. To two early figures—John Galt and Benjamin Rush—whose ideas helped define the trajectory of an entire field. What we find there presents a choice: a path toward genuine hope, or a legacy of continued harm.

This story takes us into the forgotten corners of that history, a place where “normal” and “abnormal” were declared not by discovery, but by decree.

Clinical psychiatrist Paul Minot put it plainly:

“Psychiatry is so ashamed of its history that it has deleted much of it.”

And for good reason.

Psychiatry’s early roots weren’t just tangled with bad science—they were soaked in ideology. What passed for “treatment” was often social control, justified through a veneer of medical language. Institutions were built not to heal, but to hide. Lives were labeled defective.

We would like to think that medicine is objective, that the white coat stands for healing. But behind those coats was a mission to save society from the so-called “abnormal.”

But who defined normal?

And who paid the price?

The Forgotten Legacy of Dr. John Galt

Long before DSM codes and Big Pharma, the first freestanding mental hospital in America called Eastern Lunatic Asylum opened its doors in 1773—just down the road from where I live, in Williamsburg, Virginia. Though officially declared a hospital, it was commonly known as “The Madhouse.” For most who entered, institutionalization meant isolation, dehumanization, and often treatment worse than what was afforded to livestock. Mental illness was framed as a threat to the social order—those deemed “abnormal” were removed from society and punished in the name of care.

But one man dared to imagine something different.

Dr. John Galt II, appointed as the first medical superintendent of the hospital (later known as Eastern State), came from a family of alienists—an old-fashioned term for early psychiatrists. The word comes from the Latin alienus, meaning “other” or “stranger,” and referred to those considered mentally “alienated” from themselves or society. Today, of course, the word alien has taken on very different connotations—especially in the heated political debates over immigration. It’s worth clarifying: the historical use of alienist had nothing to do with immigration or nationality. It was a clinical label tied to 19th-century psychiatry, not race or citizenship. But like many terms, it’s often misunderstood or manipulated in modern discourse.

Galt, notably, broke with the harsh legacy of many alienists of his time. Inspired by French psychiatrist Philippe Pinel—often credited as the first true psychiatrist—Galt embraced a radically compassionate model known as moral therapy. Where others saw madness as a threat to be controlled, Galt saw suffering that could be soothed. He believed the mentally ill deserved dignity, freedom, and individualized care—not chains or punishment. He refused to segregate patients by race. He treated enslaved people alongside the free. And he opposed the rising belief—already popular among his fellow psychiatrists—that madness was simply inherited, and the mad were unworthy of full personhood.

Rather than seeing madness as a biological defect to be subdued or “cured,” Galt and Pinel viewed it as a crisis of the soul. Their methods rejected medical manipulation and instead focused on restoring dignity. They believed that those struggling with mental affliction should be treated not as deviants but as ordinary people, worthy of love, freedom, and respect.

Dr. Marshall Ledger, founder and editor of Penn Medicine, once quoted historian Nancy Tomes to summarize this period:

“Medical science in this period contributed to the understanding of mental illness, but patient care improved less because of any medical advance than because of one simple factor: Christian charity and common sense.”

Galt’s asylum was one of the only institutions in the United States to treat enslaved people and free Black patients equally—and even to employ them as caregivers. He insisted that every person, regardless of race, had a soul of equal moral worth. His belief in equality and metaphysical healing put him at odds with nearly every other psychiatrist of his time.

And he paid the price.

The psychiatric establishment, closely allied with state power and emerging medical-industrial interests, rejected his human-centered model. Most psychiatrists of the era endorsed slavery and upheld racist pseudoscience. The prevailing consensus was rooted in hereditary determinism—that madness and criminality were genetically transmitted, particularly among the “unfit.”

This growing belief—that mental illness was a biological flaw to be medically managed—was not just a scientific view, but an ideological one. Had Galt’s model of moral therapy been embraced more broadly, it would have undermined the growing assumption that biology and state-run institutions offered the only path to sanity. It would have challenged the idea that human suffering could—and should—be controlled by external authorities.

Instead, psychiatry aligned with power.

Moral therapy was quietly abandoned. And the field moved steadily toward the medicalized, racialized, and state-controlled version of mental health that would pave the way for both eugenics and the modern pharmaceutical regime.

"The Father of American Psychiatry"

Long before Nazi Germany. Long before the Eugenics Record Office. Long before sterilization laws and IQ tests, there was Dr. Benjamin Rush—signer of the Declaration of Independence, founder of the first American medical school, and the man still honored as the “father of American psychiatry.” His portrait hangs today in the headquarters of the American Psychiatric Association.

Though many historians point to Francis Galton as the father of eugenics, it was Rush—nearly a century earlier—who laid much of the ideological groundwork. He argued that mental illness was biologically determined and hereditary. And he didn’t stop there.

Rush infamously diagnosed Blackness itself as a form of disease—what he called “negritude.” He theorized that Black people suffered from a kind of leprosy, and that their skin color and behavior could, in theory, be “cured.” He also tied criminality, alcoholism, and madness to inherited degeneracy, particularly among poor and non-white populations.

These ideas found a troubling ally in Charles Darwin’s emerging theories of evolution and heredity. While Darwin’s work revolutionized biology, it was often misused to justify racist notions of racial hierarchy and biological determinism.

Rush’s medical theories were mainstream and deeply influential, shaping generations of physicians and psychiatrists. Together, these ideas reinforced the belief that social deviance and mental illness were rooted in faulty bloodlines—pseudoscientific reasoning that provided a veneer of legitimacy to racism and social control within medicine and psychiatry.

The tragic irony? While Rush advocated for the humane treatment of the mentally ill in certain respects, his racial theories helped pave the way for the pathologizing of entire populations—a mindset that would fuel both American and European eugenics movements in the next century.

American Eugenics: The Soil Psychiatry Grew From

Before Hitler, there was Cold Spring Harbor. Founded in 1910, the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) operated out of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York with major funding from the Carnegie Institution, later joined by Rockefeller Foundation money. It became the central hub for American eugenic research, gathering family pedigrees to trace so-called hereditary defects like "feeblemindedness," "criminality," and "pauperism.” (extreme poverty.)

Between the early 1900s and 1970s, over 30 U.S. states passed forced sterilization laws targeting tens of thousands of people deemed unfit to reproduce. The justification? Traits like alcoholism, poverty, promiscuity, deafness, blindness, low IQ, and mental illness were cast as genetic liabilities that threatened the health of the nation.

The practice was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927 in the infamous case of Buck v. Bell. In an 8–1 decision, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough,” greenlighting the sterilization of 18-year-old Carrie Buck, a young woman institutionalized for being "feebleminded"—a label also applied to her mother and child. The ruling led to an estimated 60,000+ sterilizations across the U.S.

And yes—those sterilizations disproportionately targeted African American, Native American, and Latina women, often without informed consent. In North Carolina alone, Black women made up nearly 65% of sterilizations by the 1960s, despite being a much smaller share of the population.

Eugenics wasn’t a fringe pseudoscience. It was mainstream policy—supported by elite universities, philanthropists, politicians, and the medical establishment.

And psychiatry was its institutional partner.

The American Journal of Psychiatry published favorable discussions of sterilization and even euthanasia for the mentally ill as early as the 1930s. American psychiatrists traveled to Nazi Germany to observe and advise, and German doctors openly cited U.S. laws and scholarship as inspiration for their own racial hygiene programs.

In some cases, the United States led—and Nazi Germany followed.

This isn’t conspiracy. It’s history. Documented, peer-reviewed, and disturbingly overlooked.

From Ideology to Institution

By the early 20th century, the groundwork had been laid. Psychiatry had evolved from a fringe field rooted in speculation and racial ideology into a powerful institutional force—backed by universities, governments, and the courts. But its foundation was still deeply compromised. What had begun with Benjamin Rush’s biologically deterministic theories and America’s eugenic policies now matured into a formalized doctrine—one that treated human suffering not as a relational or spiritual crisis, but as a defect to be categorized, corrected, or eliminated.

This is where the five core doctrines of modern psychiatry emerge.

The Five Doctrines That Shaped Modern Psychiatry

These five doctrines weren’t abandoned after World War II. They were rebranded, exported, and quietly absorbed into the foundations of American psychiatry.

1. The Elimination of Subjectivity

Patients were no longer seen as people with stories, pain, or meaning—they were seen as bundles of symptoms. Suffering was abstracted into clinical checklists. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) became the gold standard, not because it offered clear science, but because it offered utility: a standardized language that served pharmaceutical companies, insurance billing, and bureaucratic control. If you could name it, you could code it—and medicate it.

2. The Eradication of Spiritual and Moral Meaning

Struggles once understood through relational, existential, or moral frameworks were stripped of depth. Grief became depression. Anger became oppositional defiance. Existential despair was reduced to a neurotransmitter imbalance. The soul was erased from the conversation. As Berger notes, suffering was no longer something to be witnessed or explored—it became something to be treated, as quickly and quietly as possible.

3. Biological Determinism

Mental illness was redefined as the inevitable result of faulty genes or broken brain chemistry—even though no consistent biological markers have ever been found. The “chemical imbalance” theory, aggressively marketed throughout the late 20th century, was never scientifically validated. Yet it persists, in part because it sells. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—still widely prescribed—were promoted on this flawed premise, despite studies showing they often perform no better than placebo and come with serious side effects, including emotional blunting, dependence, and sexual dysfunction.

4. Population Control and Racial Hygiene

In Germany, this meant sterilizing and exterminating those labeled “life unworthy of life.” In the U.S., it meant forced sterilizations of African American and Native American women, institutionalizing the poor, the disabled, and the nonconforming. These weren’t fringe policies—they were mainstream, upheld by law and supported by leading psychiatrists and journals. Even today, disproportionate diagnoses in communities of color, coercive treatments in prisons and state hospitals, and medicalization of poverty reflect these same logics of control.

5. The Use of Institutions for Social Order

Hospitals became tools for enforcing conformity. Psychiatry wasn’t just about healing—it was about managing the unmanageable, quieting the inconvenient, and keeping society orderly. From lobotomies to electroshock therapy to modern-day involuntary holds, psychiatry has long straddled the line between medicine and discipline. Coercive treatment continues under new names: community treatment orders, chemical restraints, and state-mandated compliance.

These doctrines weren’t discarded after the fall of Nazi Germany. They were imported. Adopted. Rebranded under the guise of “evidence-based medicine” and “public health.” But the same logic persists: reduce the person, erase the context, medicalize the soul, and reinforce the system.

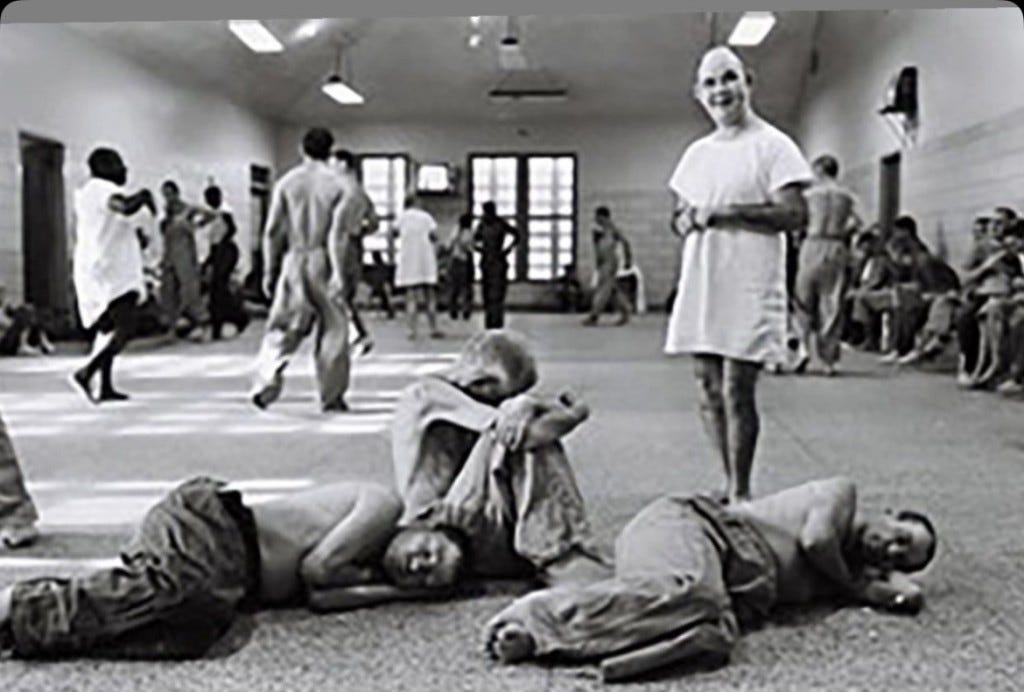

Letchworth Village: The Human Cost

I didn’t simply read this in a textbook. I stood there—on the edge of those woods—next to rows of numbered graves.

In 2020, while waiting to close on our New York house, my husband and I were staying in an Airbnb in Rockland County. We were walking the dogs one morning nearing the end of Call Hollow Road, there is a wide path dividing thick woodland when we came across a memorial stone:

“THOSE WHO SHALL NOT BE FORGOTTEN.”

We had stumbled upon the entrance to Old Letchworth Village Cemetery, and we instantly felt it's somber history. Beyond it, rows of T-shaped markers each one a muted testament to the hundreds of nameless victims who perished at Letchworth. Situated just half a mile from the institution, these weathered grave markers reveal only the numbers that were once assigned to forgotten souls—a stark reminder that families once refused to let their names be known.

When we researched the history, the truth was staggering.

Letchworth was supposed to be a progressive alternative to the horrors of 19th-century asylums. Instead, it became one of them. By the 1920s, reports described children and adults left unclothed, unbathed, overmedicated, and raped. Staff abused residents—and each other. The dormitories were overcrowded. Funding dried up. Buildings decayed.

The facility was severely overcrowded. Many residents lived in filth, unfed and unattended. Children were restrained for hours. Some were used in vaccine trials without consent. And when they died, they were buried behind the trees—nameless, marked only by small concrete stakes.

I stood among those graves. Over 900 of them. A long row of numbered markers, each representing a life once deemed unworthy of attention, of love, of dignity.

But the deeper horror is what Letchworth symbolized: the idea that certain people were better off warehoused than welcomed, that abnormality was a disease to be eradicated—not a difference to be understood.

This is the real history of psychiatric care in America.

The Problem of Purpose

But this history didn’t unfold in a vacuum. It was built on something deeper—an idea so foundational, it often goes unquestioned: that nature has no purpose. That life has no inherent meaning. That humans are complex machines—repairable, discardable, programmable.

This mechanistic worldview didn’t just shape medicine. It has shaped what we call reality itself.

As Dr. Rupert Sheldrake explains in Science Set Free, the denial of purpose in biology isn’t a scientific conclusion—it’s a philosophical assumption. Beginning in the 17th century, science removed soul and purpose from nature. Plants, animals, and human bodies were understood as nothing more than matter in motion, governed by fixed laws. No pull toward the good. No inner meaning.

By the time Darwin’s Origin of Species arrived in the 19th century 1859, this mechanistic lens was fully established. Evolution wasn’t creative—it was random. Life wasn’t guided—it was accidental.

Psychiatry, emerging in this same cultural moment, absorbed this worldview. Suffering was pathologized, difference diagnosed, and the soul reduced to faulty genetics and broken wiring.

Today, that mindset is alive in the DSM’s ever-expanding labels, in the belief that trauma is a chemical imbalance, that identity issues must be solved with hormones and surgery, and in the reflex to medicate children who don’t conform.

But what if suffering isn’t a bug in the system?

What if it’s a signal?

What if these so-called “disorders” are cries for meaning in a world that pretends meaning doesn’t exist?

The graves at Letchworth aren’t just a warning about medical abuse. They are a mirror—reflecting what happens when we forget that people are not problems to be solved, but souls to be seen.

Sheldrake writes, “The materialist denial of purpose in evolution is not based on evidence but is an assumption.” Modern science insists all change results from random mutations and blind forces—chance and necessity. But these claims are not just about biology. They influence how we see human beings: as broken machines to be repaired or discarded.

As we said, in the 17th century, the mechanistic revolution abolished soul and purpose from nature—except in humans. But as atheism and materialism rose in the 19th century, even divine and human purpose were dismissed, replaced by the ideal of scientific “progress.” Psychiatry emerged from this philosophical soup, fueled not by reverence for the human soul but by the desire to categorize, control, and “correct” behavior—by any mechanical means necessary.

What if that assumption is wrong? What if the people we label “disordered” are responding to something real? What if our suffering has meaning—and our biology is not destiny?

“Genetics” as the New Eugenics

Today, psychiatry no longer speaks in the language of race hygiene.

It speaks in the language of genes.

But the message is largely the same:

You are broken at the root.

Your biology is flawed.

And the only solution is lifelong medication—or medical intervention.

We now tell people their suffering is rooted in faulty wiring, inherited defects, or bad brain chemistry—despite decades of inconclusive or contradictory evidence.

We still medicalize behaviors that don’t conform.

We still pathologize pain that stems from trauma, poverty, or social disconnection.

We still market drugs for “chemical imbalances” that have never been biologically verified.

And we still pretend this is science—not ideology.

But as Dr. Rupert Sheldrake argues in Science Set Free, even the field of genetics rests on a fragile and often overstated foundation. In Chapter 6, he challenges one of modern biology’s core assumptions: that all heredity is purely material—that our traits, tendencies, and identities are completely locked in by our genes.

But this isn’t how people have understood inheritance for most of human history.

Long before Darwin or Mendel, breeders, farmers, and herders knew how to pass on traits. Proverbs like “like father, like son” weren’t based on lab results—they were based on generations of observation. Dogs were bred into dozens of varieties. Wild cabbage became broccoli, kale, and cauliflower. The principles of heredity weren’t discovered by science; they were named by science. They were already in practice across the world.

What Sheldrake points out is that modern biology took this folk knowledge, stripped it of its nuance, and then centralized it—until genes became the sole explanation for almost everything.

And that’s a problem.

Because genetics has been crowned the ultimate cause of everything from depression to addiction, from ADHD to schizophrenia. When the outcomes aren’t clear-cut, the answer is simply: “We haven’t mapped the genome enough yet.”

But what if the model is wrong?

What if suffering isn’t locked in our DNA?

What if genes are only part of the story—and not even the most important part?

By insisting that people are genetically flawed, psychiatry sidesteps the deeper questions:

What happened to you?

What story are you carrying?

What environments shaped your experience of the world?

It pathologizes people—and exonerates systems.

Instead of exploring trauma, we prescribe pills.

Instead of restoring dignity, we reduce people to diagnoses.

Instead of healing souls, we treat symptoms.

Modern genetics, like eugenics before it, promises answers. But too often, it delivers a verdict: you were born broken.

We can do better.

We must do better.

Because healing doesn’t come from blaming bloodlines or rebranding biology.

It comes from listening, loving, and refusing to reduce people to a diagnosis or a gene sequence.

The Hidden Truth About Trauma and Diagnosis

As Pete Walker references Dr. John Briere’s poignant observation: if Complex PTSD and the role of early trauma were fully acknowledged by psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) could shrink from a massive textbook to something no larger than a simple pamphlet.

We’ve previously explored the crucial difference between PTSD and complex PTSD—topics like trauma, identity, neuroplasticity, stress, survival, and what it truly means to come home to yourself. This deeper understanding exposes a vast gap between real human experience and how mental health is often diagnosed and treated today.

Instead of addressing trauma with truth and compassion, the system expands diagnostic categories, medicalizes pain, and silences those who suffer.

The Cost of Our Silence

Many of us know someone who’s been diagnosed, hospitalized, or medicated into submission.

Some of us have been that person.

And we’re told this is progress. That this is compassion. That this is care.

But when I stood at the edge of those graves in Rockland County—row after row of anonymous markers—nothing about this history felt compassionate.

It felt buried. On purpose.

We must unearth it.

Not to deny mental suffering—but to reclaim the right to define it for ourselves.

To reimagine what healing could look like, if we dared to value dignity over diagnosis.

Because psychiatry hasn’t “saved” the abnormal.

It has often silenced, sterilized, and sacrificed them.

It has named pain as disorder.

Difference as defect.

Trauma as pathology.

The DSM is not a Bible.

The white coat is not a priesthood.

And genetics is not destiny.

We need better language, better questions, and better ways of relating to each other’s pain.

And that brings us full circle—to a man most people have never heard of: Dr. John Galt II.

Nearly 200 years ago, in Williamsburg, Virginia, Galt ran the first freestanding mental hospital in America. But unlike many of his peers, he rejected chains, cruelty, and coercion. He embraced what he called moral treatment—an approach rooted in truth, love, and human dignity. Galt didn’t see the “insane” as dangerous or defective. He saw them as souls.

He was influenced by Philippe Pinel, the French physician who famously removed shackles from asylum patients in Paris. Together, these early reformers dared to believe that healing began not with force, but with presence. With relationship. With care.

Galt refused to segregate patients by race. He treated enslaved people alongside the free. And he opposed the rising belief—already popular among his fellow psychiatrists—that madness was simply inherited, and the mad were unworthy of full personhood.

But what does it mean to recognize someone’s personhood?

Personhood is more than just being alive or having a body. It’s about being seen as a full human being with inherent dignity, moral worth, and rights—someone whose inner life, choices, and experiences matter. Recognizing personhood means acknowledging the whole person beyond any diagnosis, disability, or social status.

This question isn’t just philosophical—it’s deeply practical and contested. It’s at the heart of debates over mental health care, disability rights, euthanasia and even abortion. When does a baby become a person? When does someone with a mental illness or cognitive difference gain full moral consideration? These debates all circle back to how we define humanity itself.

In Losing Our Dignity: How Secularized Medicine Is Undermining Fundamental Human Equality, Charles C. Camosy warns that secular, mechanistic medicine can strip people down to biological parts—genes, symptoms, behaviors—rather than seeing them as full persons. This reduction risks denying people their dignity and the respect that comes with being more than the sum of their medical conditions.

Galt’s approach stood against this reduction. He saw patients as complex individuals with stories and struggles, deserving compassion and respect—not just as “cases” to be categorized or “disorders” to be fixed.

To truly recognize personhood is to honor that complexity and to affirm that every individual, regardless of race, mental health, or social status, has an equal claim to dignity and care.

But… Galt’s approach was pushed aside.

Why?

Because it didn’t serve the state.

Because it didn’t serve power.

Because it didn’t make money.

Today, we see a similar rejection of truth and compassion.

When a child in distress is told they were “born in the wrong body,” we call it gender-affirming care.

When a woman, desperate to be understood, is handed a borderline personality disorder label instead.

When medications with severe side effects are pushed as the only solution, we call it science.

But are we healing the person—or managing the symptoms?

Are we meeting the soul—or erasing it?

We’ve medicalized the human condition—and too often, we’ve called that progress.

We’ve spoken before about the damage done by Biblical counseling programs when therapy is replaced with doctrine—how evangelical frameworks often dismiss pain as rebellion, frame anger as sin, and pressure survivors into premature forgiveness.

But the secular system is often no better. A model that sees people as nothing more than biology and brain chemistry may wear a lab coat instead of a collar—but it still demands submission.

Both systems can bypass the human being in front of them.

Both can serve control over compassion.

Both can silence pain in the name of order.

What we truly need is something deeper.

To be seen.

To be heard.

To be honored in our complexity—not reduced to a diagnosis or a moral failing.

It’s time to stop.

It’s time to remember that human suffering is not a clinical flaw. It’s time to remember the metaphysical soul/psyche.

Our emotional pain is not a chemical defect.

That being different, distressed, or deeply wounded is not a disease.

It’s time to recover the wisdom of Dr. John Galt II.

To treat those in pain—not as problems to be solved—but as people to be seen.

To offer truth and love, not labels, not sterilizing surgeries and lifelong prescriptions.

Because if we don’t, the graves will keep multiplying—quietly, behind institutions, beneath a silence we dare not disturb.

But we must disturb it.

Because they mattered.

And truth matters.

And the most powerful medicine has never been compliance or chemistry.

It’s being met with real humanity.

Being listened to. Believed.

Not pathologized. Not preached at. Not controlled.

But loved—in the deepest, most grounded sense of the word.

The kind of love that doesn’t look away.

The kind that tells the truth, even when it’s costly.

The kind that says: you are not broken—you are worth staying with.

Because to love someone like that…

is to recognize their humanity.

And maybe that’s the most radical act of all.

SOURCES:

"Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics from 1927 to 1942, [Eugen] Fischer authored a 1913 study of the Mischlinge (racially mixed) children of Dutch men and Hottentot women in German southwest Africa. Fischer opposed 'racial mixing, arguing that "negro blood" was of 'lesser value and that mixing it with 'white blood' would bring about the demise of European culture" (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race," HMM Online: https://www.ushmm.org/exhibition/deadly-medicine/ profiles/). See also, Richard C. Lewontin, Steven Rose, and Leon J. Kamin, Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology, and Human Nature 2nd edition (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 207.

Gonaver, The Making of Modern Psychiatry

Saving Abnormal-The Disorder of Psychiatric Genetics-Daneil R Berger II

Lost Architecture: Eastern State Hospital - Colonial Williamsburg

📘 General History of American Eugenics

Lombardo, Paul A.

Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell (2008)

This book is the definitive account of Buck v. Bell and American eugenics law. It documents how widespread sterilizations were and provides legal and historical context.

Black, Edwin.

War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race (2003)

Covers the U.S. eugenics movement in depth, including funding by Carnegie and Rockefeller, Cold Spring Harbor, and connections to Nazi Germany.

Kevles, Daniel J.

In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (1985)

A foundational academic history detailing how early American psychiatry and genetics were interwoven with eugenic ideology.

🧬 Institutions & Funding

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives

https://www.cshl.edu

Documents the history of the Eugenics Record Office (1910–1939), its funding by the Carnegie Institution, and its influence on U.S. and international eugenics.

The Rockefeller Foundation Archives

https://rockarch.org

Shows how the foundation funded eugenics research both in the U.S. and abroad, including programs that influenced German racial hygiene policies.

⚖️ Sterilization Policies & Buck v. Bell

Supreme Court Decision: Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927)

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/274/200/

Includes Justice Holmes’ infamous quote and the legal justification for forced sterilization.

North Carolina Justice for Sterilization Victims Foundation

https://www.ncdhhs.gov

Reports the disproportionate targeting of Black women in 20th-century sterilization programs.

Stern, Alexandra Minna.

Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (2005)

Explores race, sterilization, and medical ethics in eugenics programs, with data from states like California and North Carolina.

🧠 Psychiatry’s Role & Nazi Connections

Lifton, Robert Jay.

The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide (1986)

Shows how American eugenics—including psychiatric writings—helped shape Nazi ideology and policies like Aktion T-4 (the euthanasia program).

Wahl, Otto F.

“Eugenics, Genetics, and the Minority Group Mentality” in American Journal of Psychiatry, 1985.

Traces how psychiatric institutions were complicit in promoting eugenic ideas.

American Journal of Psychiatry Archives

1920s–1930s issues include articles in support of sterilization and early euthanasia rhetoric.

Available via https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org

Share this post