Welcome back to Taste Test Thursdays where we're exploring the topics that didn't make it to the main dish Taste0ftruth Tuesdays and today I wanted to talk about a subject that I'm personally very fascinated in which is the early 1900s. There was so much going on in regard to industry, science and faith that laid the groundwork to where we are in society.

As we stand at the crossroads of past lessons and future possibilities, the stakes have never been higher. The very systems that were once “celebrated” that industrialized food production-have increasingly revealed their darker sides. Today, the food we consume is shaped not solely by nutritional science or culinary tradition but by corporate agendas and regulatory loopholes that have been allowed corruption to flourish unchecked.

But how did we get here exactly? I won’t claim to have all the answers, but I have fallen down quite the rabbit hole in trying to cnnect all the dots. Let’s unravel how these massive cultural and technological shifts—from the Industrial Revolution to the rise of modern medicine and the spiritual reformations of the day—intertwined in ways that still echo in our health systems, food choices, and moral frameworks.

How Science, Industry, and Faith Influenced Big Food

Imagine stepping into a bustling city in the late 19th century. Horse-drawn carts rattle over cobblestone streets, factory smokestacks pump soot into a sky laced with new electric wires, and the scent of coal mingles with fresh bread from the corner bakery. The air hums with transformation. The industrial revolution isn’t just changing how people work—it’s redefining how they live, eat, and think. Machines are no longer just tools; they’ve become symbols of progress, power, and promise. This is a world charging full speed ahead toward modernity.

The Scientific Revolution and the Birth of Empiricism

In tandem with this industrial surge, a quieter—but equally radical—revolution was taking place in the halls of academia and medicine. The early 1800s marked the emergence of a new identity: the scientist. This wasn’t just a tinkerer in a lab coat, but a rigorous seeker of truth grounded in observation, measurement, and replication. Institutions like the Royal Society in Britain cultivated a new cultural reverence for empirical knowledge—knowledge that could be proven, published, and patented. Science began to replace tradition and folklore, not just in medicine but in agriculture and nutrition as well. To be modern, increasingly, was to be "scientific."

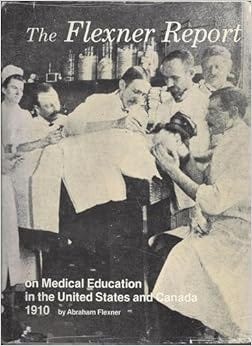

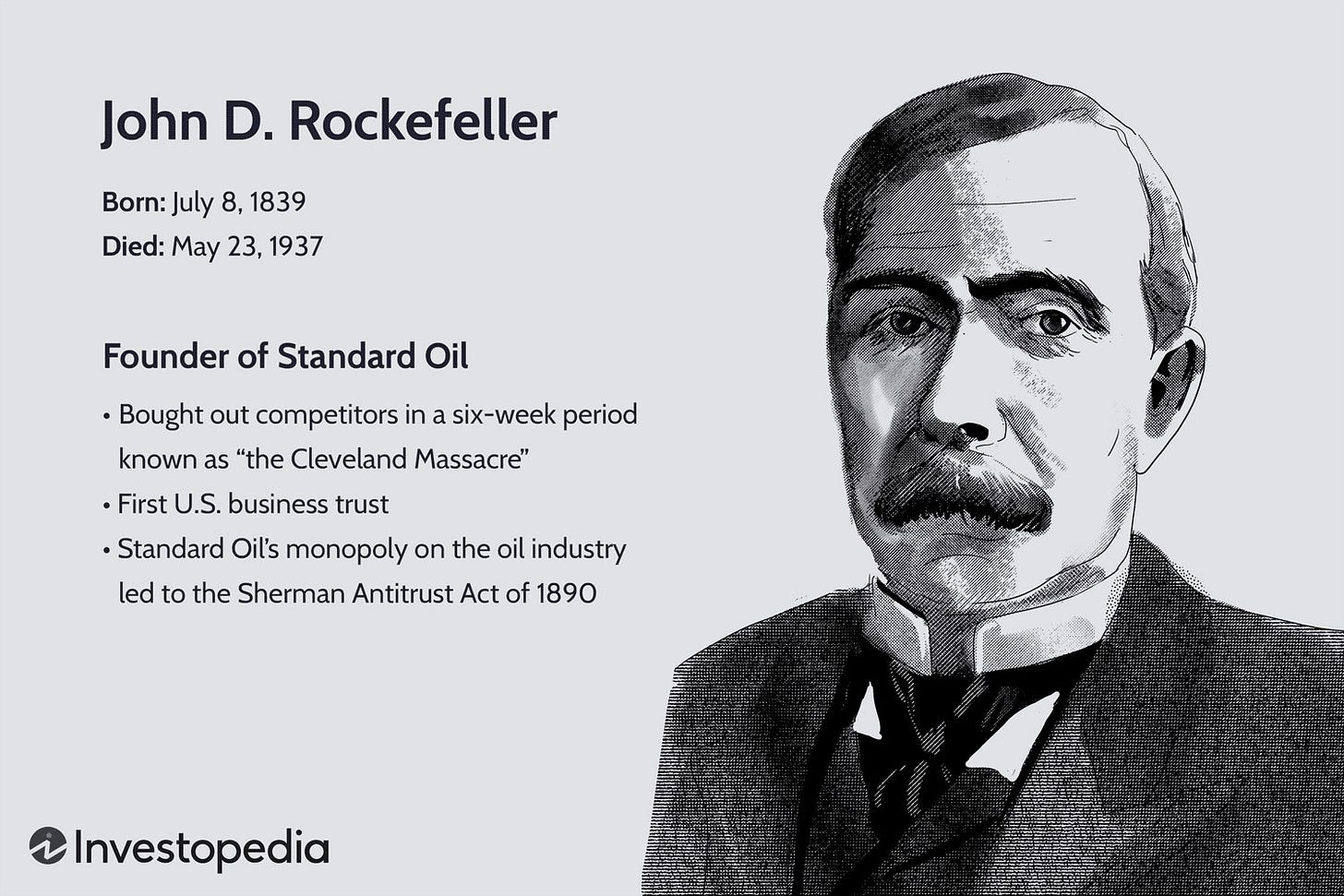

The Flexner Report and How Rockefeller Changed Nutrition

This shift toward scientific authority came to dominate American medicine in the early 20th century. In 1910, the Flexner Report, funded by the Carnegie Foundation and backed by Rockefeller money, delivered a harsh critique of the state of medical education in the United States. It demanded reform, calling for a curriculum rooted in laboratory science and pharmacology—and it succeeded. Schools that emphasized herbal remedies, homeopathy, or nutrition-based healing were discredited or shut down.

The Rockefeller Foundation, with deep interests in oil-derived pharmaceuticals, invested heavily in this new medical model. Holistic and food-based approaches were pushed to the margins, replaced by a system that favored prescriptions over prevention. It wasn't just a shift in science—it was a redirection of public trust, away from ancestral wisdom and toward corporate-sponsored expertise.

Cottonseed Oil and the Rise of Crisco

As medicine turned toward chemistry, so did the kitchen. For most of the 19th century, cotton seeds were a nuisance byproduct of cotton production, often left to rot because the oil extracted from them was dark, smelly, and unappealing.

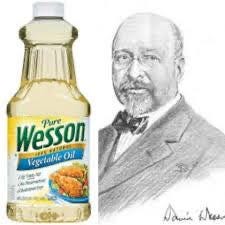

The transformation of cottonseed oil into a consumer-friendly product came about through industrial processes like bleaching and deodorizing, pioneered by chemists like David Wesson in the late 19th century. This process turns cottonseed oil clear, tasteless and neutral smelling enough to appeal to consumers. Soon, companies were selling cottonseed oil by itself as a liquid or mixing it with animal fats to make cheap, solid shortenings, sold in pails to resemble lard.

Industrializing Food: The Convergence of Chemistry and Convenience

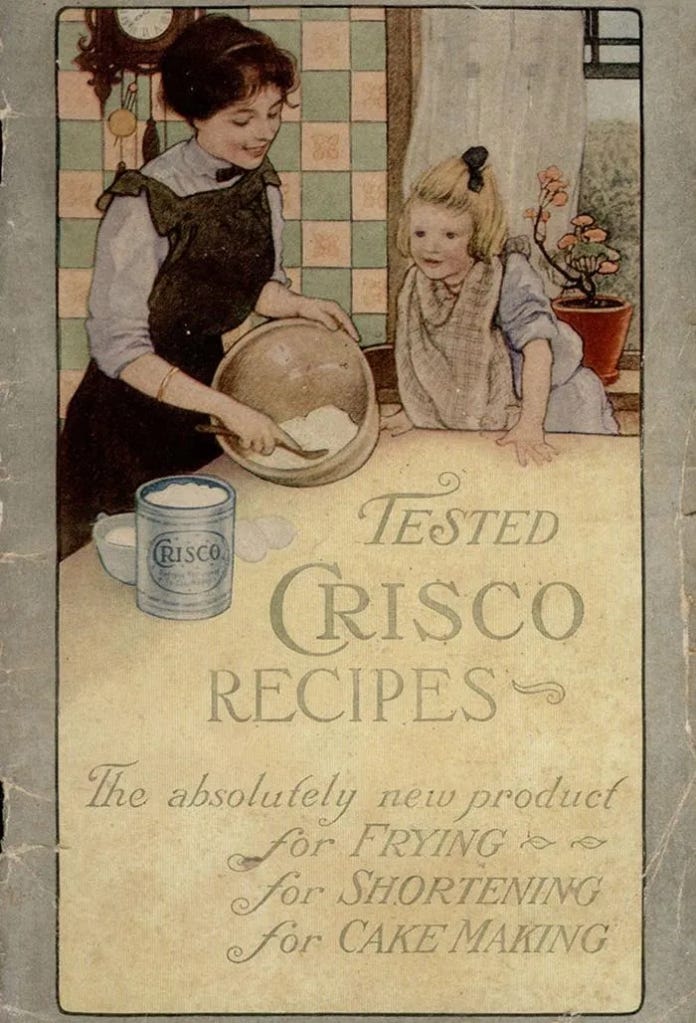

In 1911, Procter & Gamble introduced Crisco, the first hydrogenated vegetable oil, made from cottonseed. The same chemical processes used in oil refining were now repurposed to manufacture food. Crisco was marketed as a cleaner, modern alternative to animal fats like lard, its pristine white color and long shelf life pitched as signs of purity and progress.

Consumers embraced it. After all, industrialized food seemed like a miracle of modern living—cheaper, faster, and immune to spoilage. But what they didn’t know was that hydrogenation also introduced trans fats into the diet, now known to increase the risk of heart disease and inflammation. It wasn’t until decades later that the long-term health consequences became clear. By then, the machinery of food production—and the marketing engines behind it—had become nearly impossible to untangle from daily life.

Marketing and Public Perception

This shift within the approach to nutrition in medical education meant that doctors were largely untrained in the importance of diet and the health risks associated with processed foods like Crisco. As a result, the medical community was slow to recognize the dangers of trans fats, allowing products like Crisco to be marketed as healthy alternatives to natural animal fats for decades. Crisco’s success was largely driven by Procter & Gamble's brilliant marketing, which played into the themes of progress and modernity. By promoting Crisco as a superior, healthier alternative to animal fats, they helped shift public perception and dietary habits, despite the fact that Crisco was loaded with trans fats—now known to be harmful to cardiovascular health.

Shortening’s main rival was lard. Earlier generations of Americans had produced lard at home after autumn pig slaughters, but by the late 19th century meat processing companies were making lard on an industrial scale. Lard had a noticeable pork taste, but there’s not much evidence that 19th-century Americans objected to it, even in cakes and pies. Instead, its issue was cost. While lard prices stayed relatively high through the early 20th century, cottonseed oil was abundant and cheap.

Nonetheless, early cottonseed oil and shortening companies went out of their way to highlight their connection to cotton. They touted the transformation of cottonseed from pesky leftover to useful consumer product as a mark of ingenuity and progress.

Proctor and Gamble's brilliant marketing campaign for the original Crisco, an alternative to lard that went on sale in 1911. "It's all vegetable! It's digestible!" it proclaimed. Procter & Gamble convinced people to forgo butter and lard for cheap, factory-made oils loaded with trans-fat. Crisco flew off the shelves. Unlike lard, Crisco had a neutral taste. Unlike butter, Crisco could last for years on the shelf. Unlike olive oil, it had a high smoking temperature for frying. At the same time, since Crisco was the only solid shortening made entirely from plants, it was prized by Jewish consumers who followed dietary restriction.

The Spiritual Renaissance and the Second Great Awakening

As machines and scientific breakthroughs took center stage, spirituality was undergoing its own profound transformation. The Second Great Awakening swept across America, inspiring individuals to seek a personal, emotional connection with the divine. Preachers like Charles Finney broke the mold by challenging the necessity of institutional intermediaries, urging people to experience faith directly and passionately. This personal form of religion not only gave rise to social reform movements—such as abolition, women’s rights, and temperance—but also laid the foundations for a holistic approach to well-being.

Food as a Sacred Ritual

Long before the wellness industry rebranded food as medicine, religious reformers in America were already preaching that diet was a spiritual matter. In the mid-19th century, the Seventh-Day Adventist Church emerged as a major force in reshaping American dietary culture. For key figures like Ellen G. White, food wasn’t just about physical nourishment—it was a tool for cultivating spiritual purity and moral discipline. She advocated for vegetarianism, abstinence from stimulants like caffeine and alcohol, and a holistic approach to health, all rooted in divine revelation rather than scientific evidence.

These ideas were institutionalized through Adventist-run facilities like the Battle Creek Sanitarium, led by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg. Under his leadership, diet and disease prevention became central pillars of care. Kellogg carried White’s teachings into mainstream health culture, helping to normalize plant-based diets and whole foods. Their influence stretched beyond religious circles, contributing to the formation of the American Dietetic Association in 1917, which originally promoted many of these dietary ideals. Though framed as health science, much of this early nutrition advice was infused with theological morality, not empirical data.

But the Adventists weren’t the only ones moralizing mealtime.

Decades earlier, Sylvester Graham—a Presbyterian minister and the namesake of the Graham cracker—launched his own health reform crusade. Like White, he believed that food influenced not just the body but the soul. Graham promoted a simple, vegetarian diet free from stimulants, claiming it could suppress sexual urges and promote moral restraint. His infamous cracker wasn’t a sweet treat—it was a spiritual safeguard designed to dull desire and support digestive health. Graham’s approach to nutrition was grounded in purity culture, with dietary control used as a tool for policing behavior.

Both Graham and the Adventists helped establish food as a kind of moral technology—a means of shaping not just health outcomes but character, discipline, and righteousness. Their legacies persist today, hidden beneath modern trends like veganism, detoxing, and clean eating. While some of their insights into whole foods and preventive care align with contemporary evidence-based guidelines, their foundational motivations were anything but neutral.

As we unpack the history of nutrition, it’s clear that much of what we now call “health advice” was originally crafted through the lens of religious and moral ideologies.

Understanding this helps us ask harder questions: How much of today’s diet culture is truly about health—and how much of it is a modern echo of old attempts to control the body in order to purify the soul?

The Rise-and the Controversy-of Modern Nutritional Advice: Ancel Keys and the Flawed Narrative on Fats

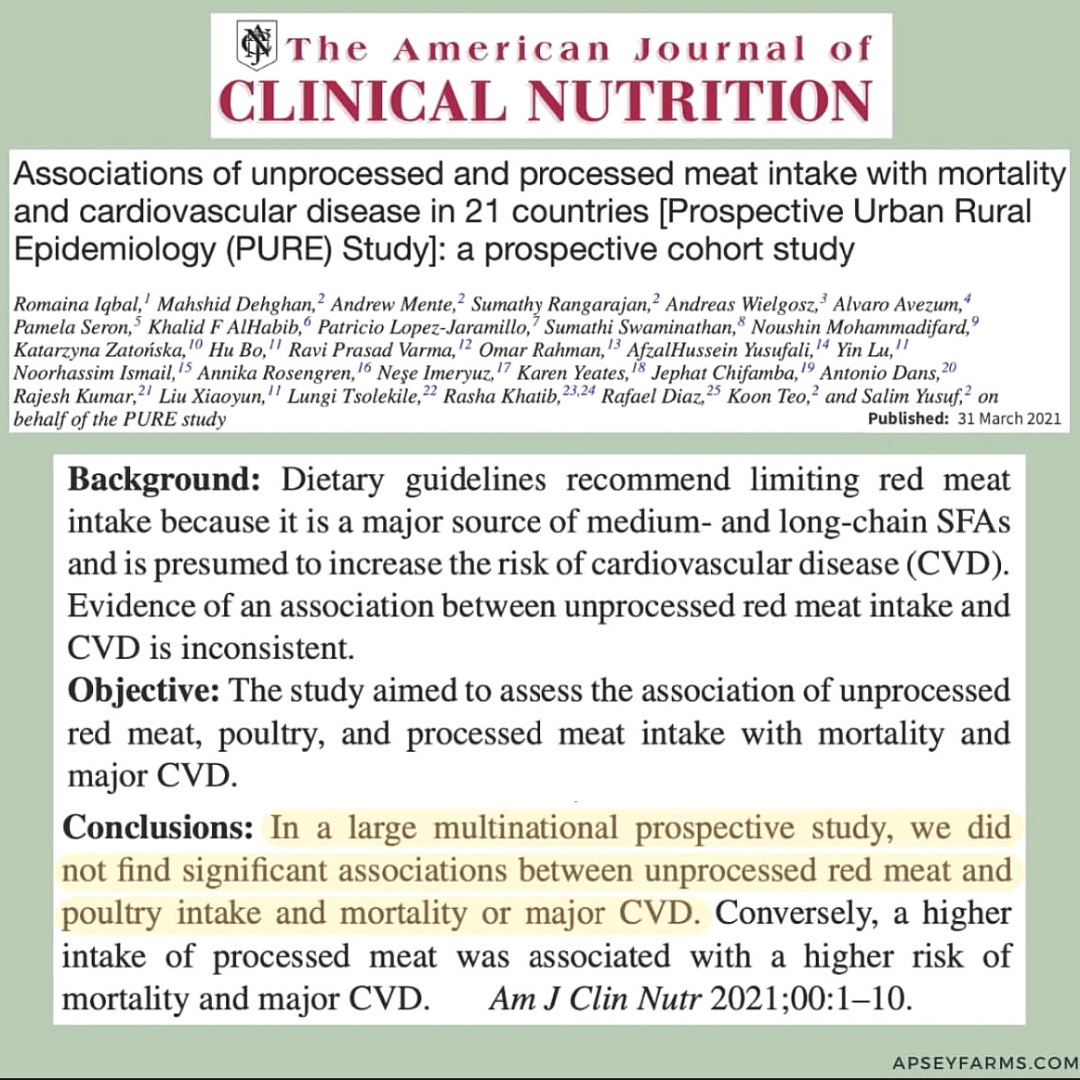

In the mid-20th century, nutritional science took center stage with figures like Ancel Keys. His influential Seven Countries Study, beginning in 1958, linked dietary fats—especially saturated fats—to heart disease. This research shaped dietary guidelines for decades, advocating low-fat diets as a preventive measure against cardiovascular disease.

However, more recent research has challenged this view, showing that reducing saturated fat intake does not have a significant impact on cardiovascular disease or mortality. In fact, some studies have found that saturated fats may have protective effects against stroke, and that unprocessed red meat and whole-fat dairy are not associated with increased risks of heart disease or early death.

Read more about his cherry-picked, flawed research.

The Industrialization of Food and the Consequences

The rise of Crisco and other processed foods, combined with the medical community's neglect of nutrition, contributed to the industrialization of the American diet. This shift led to an increased consumption of processed, nutrient-poor foods, which has been linked to the rise of chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. The influence of flawed research and powerful marketing campaigns led to widespread misconceptions about the healthfulness of different types of fats, resulting in dietary guidelines that favored industrial products over natural, whole foods.

Why “Trust the Experts” Is Failing Us: Corporate Agendas and Hidden Loopholes

The Corporate Seepage in Public Health

In today’s world, the echoes of past transformations continue to challenge us. A 2020 study revealed a startling fact: 95% of the members on the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee—tasked with informing our national health policies—had ties with industry giants like Kellogg, General Mills, Kraft, and Dannon. Research funding, board connections, and other conflicts of interest now cast doubt on the impartiality of public health recommendations. When the very experts entrusted with safeguarding our well-being are enmeshed in corporate interests, the promise of unbiased, independent guidance begins to crumble.

The GRAS Loophole: Letting the Fox Guard the Henhouse

Between 2000 and 2021, a staggering 766 new chemicals entered the U.S. food supply. Even more concerning is that 98.7% of these chemicals were approved via the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) pathway—a system that allows companies to self-certify the safety of their products without rigorous FDA oversight. This loophole effectively means that many additives in our favorite foods—from artificial colors and preservatives to flavor enhancers—are introduced to the market without independent, comprehensive safety evaluations.

RFK Jr.: Dragging the Health Conversation to a National Stage

In response to these revelations, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has emerged as a vital, though controversial, advocate for change. By challenging the dominance of artificial food dyes and the unchecked influence of chemical additives, RFK has successfully dragged the health conversation onto a national platform. His efforts remind us that the discussion about our food system isn’t merely academic—it affects real lives.

Kennedy’s endeavors have sparked a widespread reassessment of our dietary choices: People are now questioning the ingredients in drive-through meals and scrutinizing the fluorescent hues of sports drinks and snacks. The call is simple yet profound: Clean food is not a partisan issue; it is a human right. If reducing toxins and promoting transparency in our food supply is beneficial for public health, why should it become subject to political debates?

Final Reflections: Reclaiming a Holistic Vision for the Future

Our journey from the industrial age to the present day reveals a tapestry woven with ambition, innovation, controversy, and a relentless pursuit of progress. From the steel structures that defined city skylines to the laboratories that redefined human biology, and from the personal revivals in faith to the corporate strategies in our food systems, every thread of our modern fabric tells a complex story.

Today, the challenges are as real as they are intertwined: scientific breakthroughs and industrial conveniences have made life easier, yet behind the scenes, corporate interests and regulatory loopholes continue to shape the advice we receive about what we should eat, how we should live, and ultimately, how we are led to believe in our own well-being.

It is time to critically reassess the narratives handed down by “the experts.” As we question our food system—from the unchecked chemicals approved via the GRAS loophole to the conflicting interests that influence our national dietary guidelines—we must demand transparency, accountability, and a return to a more holistic approach to health.

For those wondering where to start, there are resources to help. Websites like LocalHarvest.org make it easy to find nearby farmers' markets, family farms, and CSAs (Community Supported Agriculture) in your area. Many farmers' markets even accept food stamps through the SNAP program, making fresh, local food more accessible than ever. Programs like USDA’s Farmers Market Nutrition Program (FMNP) also help connect families with nutritious, farm-fresh options.

This isn’t about fear—it’s about freedom. The freedom to nourish ourselves and our families with food we trust, to support local communities instead of faceless conglomerates, and to opt out of a system that prioritizes profit over well-being.

If there’s one truth that cuts across all lines, it’s this: Access to clean food and honest medicine shouldn’t be a luxury—it’s a basic right in a free society. When we reclaim our role as informed, self-reliant consumers, we send a clear message: progress must never come at the cost of personal liberty or human dignity. It should serve people, not just profit or power.

Sources:

📚 Further Reading

Dive deeper into these captivating topics with these resources:

The Rise and Fall of Crisco: An exploration of Crisco’s impact on the American diet.

The Forgotten Saga of Crisco: A look at the historical significance of Crisco in American food culture.

How Crisco Made Americans Believers in Industrial Food: Examining Crisco’s role in transforming American dietary habits.

Marion Nestle’s Work

Marion Nestle, a renowned nutritionist and public health advocate, has extensively written about the politics of food and how corporate interests shape food policies. Her book “Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health” is a foundational resource that explores conflicts of interest in detail. She has also published several articles and blog posts that can be found on her website, Food Politics.The Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI)

CSPI is a non-profit organization that advocates for public health and transparency in the food industry. They regularly publish reports and articles on how industry lobbyists influence dietary guidelines and public health policies. Visit their site for comprehensive resources: CSPI.The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)

JAMA has published several peer-reviewed articles on the conflicts of interest within the committees that develop dietary guidelines. You can access these studies through JAMA.The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS)

UCS focuses on the intersection of science, policy, and industry influence, and they have published reports on the food industry’s role in shaping guidelines. You can find their reports here: UCS Food System Work.Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Health Freedom Platform

RFK Jr.’s organization, Children’s Health Defense, provides reports and articles on corporate influence in healthcare and the food system. While this source may reflect RFK Jr.’s specific views, it offers insights into his arguments and data regarding industry control. Children’s Health Defense.

Center for Science in the Public Interest. (n.d.). GRAS loophole and FDA food safety concerns. https://www.cspinet.org

Environmental Working Group. (n.d.). Thousands of chemicals in our food system remain unregulated. https://www.ewg.org

LocalHarvest. (n.d.). Find local farms, farmers' markets, and CSAs. https://www.localharvest.org

Pew Charitable Trusts. (2013). Fixing the FDA’s food additive regulatory system.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). SNAP at Farmers Markets. https://www.fns.usda.gov/fmnp/overview

FDA's GRAS System: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/generally-recognized-safe-gras

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s Statements on FDA GRAS System: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2025, March 10). HHS Secretary Kennedy directs FDA to explore rulemaking to eliminate pathway for companies to self-affirm food ingredients as safe. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2025/03/10/hhs-secretary-kennedy-directs-fda-explore-rulemaking-eliminate-pathway-companies-self-affirm-food-ingredients-safe.html

Studies on Food Additives and Health Risks: National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Artificial additives and their impact on health. Artificial Food Color Additives and Child Behavior

Share this post