Welcome back to Taste of Truth Tuesdays, where we maintain our curiosity, embrace skepticism, and never stop asking what’s really going on beneath the surface.

Last week, in our episode The Deluded Brain, I prepared you for this episode by discussing Why Control Feels Safe, Certainty Feels Holy, & Complexity Feels Threatening so if you missed out, please check it out! It’s short and sweet.

Now, for today’s episode….

Let me ask you something:

Why does your body feel like it’s on high alert… even when nothing “bad” is happening?

Why do you either trust too quickly or not at all and end up anxious, burned out, and ashamed?

Why is it so damn hard to regulate your emotions, especially when you’re great at controlling everything else?

If those questions hit a little too close to home… this episode is for you.

Last season, we dove deep into complex trauma through Pete Walker’s From Surviving to Thriving, unpacking how childhood neglect, emotional abuse, and developmental trauma shape adult patterns.

And today? We’re going even deeper — through the lens of neuroscience.

Because what if these aren’t personality quirks or moral failings? What if your brain and body are actually doing their best to protect you, using adaptations wired by Complex PTSD?

My guest today is

, a neuroscience researcher and writer whose work has become a game-changer in trauma conversations. He holds a degree in Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience, has training in Internal Family Systems psychotherapy, and specializes in the emerging field of Psychoneuroimmunology — the study of how your thoughts, brain, and immune system interact.His Substack article, “PTSD & Complex PTSD Are NOT the Same Thing,” has been one of the clearest, most validating reads on this topic I’ve found.

So, if you’ve ever felt stuck, shut down, reactive, misunderstood, or like your nervous system has a mind of its own…. stay with me.

Because we’re not just talking trauma.

We’re talking nervous system intelligence.

We’re talking identity repair.

We’re talking real, embodied healing.

And before we get into that, I want to bring a few threads together from past episodes—because they’re all woven into this conversation.

We’ve talked about fawning, the lesser-known trauma response that shows up as chronic people-pleasing, self-abandonment, and conflict avoidance—especially common in those who’ve survived high-control environments.

In this episode with Theresa, we also explore the stress cycle. According to Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome, your body moves through three stages when facing ongoing stress: Alarm, Resistance, and eventually, Exhaustion. And fawning, while behavioral, can easily become your nervous system’s go-to tactic—especially during prolonged stress or in the presence of power dynamics that feel threatening.

We have talked about the Emotional Hijack and how trauma impacts the brain in this episode.

We’ve also referenced the vagus nerve, but not specifically Polyvagal Theory—but today, we’re going deeper.

Instead of seeing your stress responses as “malfunctions,” it reframes them as adaptive survival strategies. Your nervous system isn’t betraying you—it’s trying to protect you. It’s just working off old wiring.

Think of it like this:

Your nervous system is constantly scanning for cues of safety or threat—this is called neuroception. And based on what it detects, your body shifts into different states—each with a biological purpose.

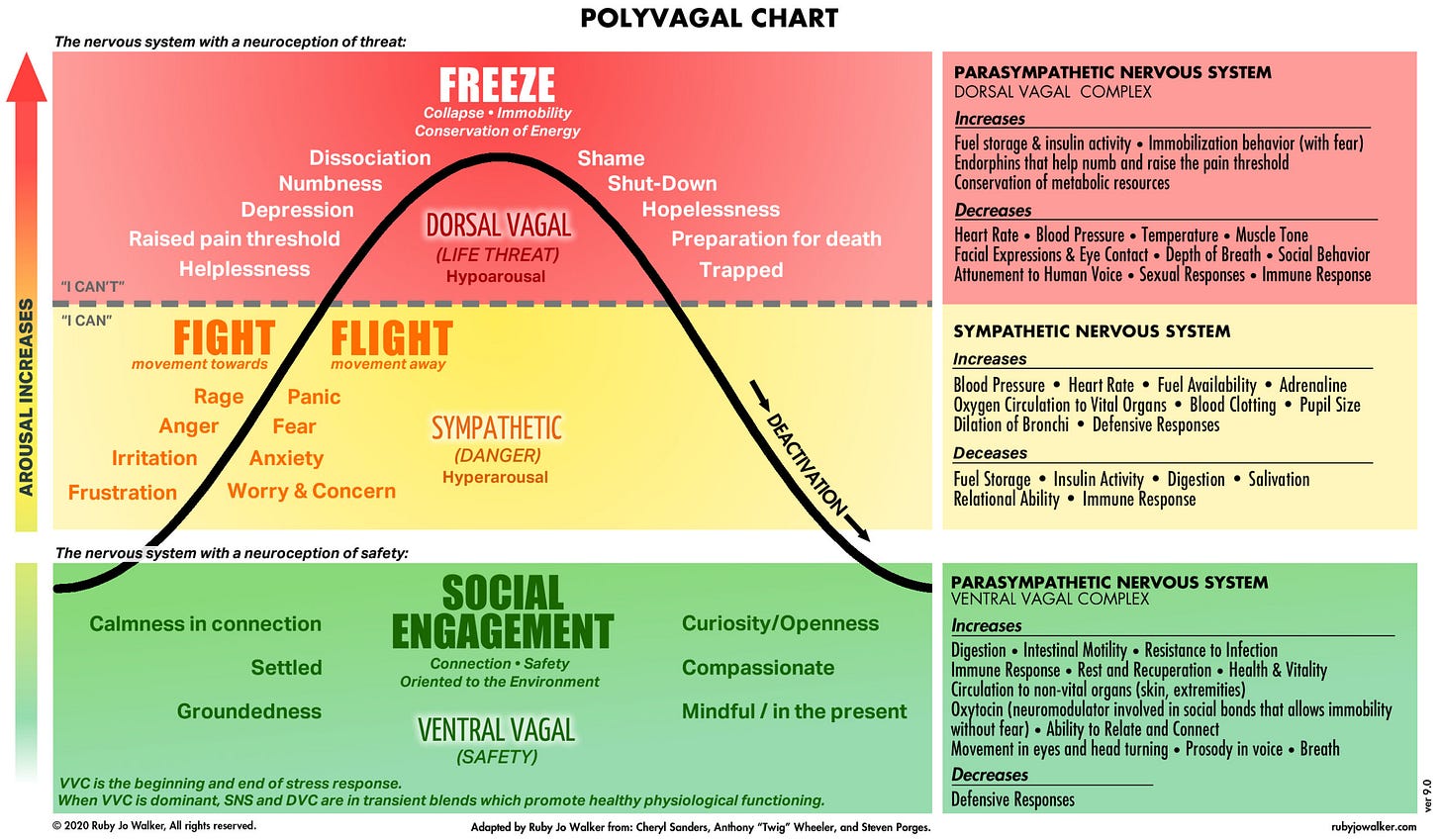

The Polyvagal Chart breaks this down into three major states:

1. 🟢 Ventral Vagal – Social Engagement (Safety)

This is your “rest-and-connect” zone. You feel grounded, calm, curious, and open. You can be present with yourself and with others. Your body prioritizes digestion, immune function, and bonding hormones like oxytocin. You’re regulated.

This is the state we’re meant to live in most of the time—but trauma, chronic stress, or inconsistent caregiving can knock us out of it.

2. 🟡 Sympathetic – Fight or Flight (Danger)

When your system detects danger, it flips into high alert. Blood rushes to your limbs, your heart races, your digestion shuts down. You either fight (rage, irritation) or flee (anxiety, panic). This is survival mode. It’s not rational—it’s reactive.

And if that still doesn’t resolve the threat?

3. 🔴 Dorsal Vagal – Freeze (Life Threat)

This is the deepest shutdown. Your system says: “This is too much. I can’t.” You go numb. You collapse. You may dissociate, feel hopeless, or emotionally flatline. It’s not weakness—it’s your nervous system pulling the emergency brake to conserve energy and protect you.

Here's what’s crucial to understand: these responses aren’t choices. They're biological defaults. And many of us are stuck in loops of fight, flight, or freeze because our systems never got a chance to complete the stress cycle and return to safety.

So instead of shaming yourself for overreacting or shutting down, what if you asked:

“What is my nervous system trying to do for me right now?”

“What does it need to feel safe again?”

That shift—from judgment to curiosity—is the beginning of healing.

And we’ll connect this to another major thread—attachment systems, which we haven’t unpacked in depth yet, but absolutely need to.

Your attachment system is the biological and psychological mechanism that drives you to seek safety, closeness, and emotional connection—especially when you’re under stress. It develops in early childhood through repeated interactions with your caregivers, shaping how you regulate your emotions, perceive threats, and relate to others. If those caregivers were emotionally attuned, predictable, and responsive, you likely formed a secure attachment. But if they were inconsistent, neglectful, controlling, or chaotic… your attachment system learned to adapt in ways that may have kept you safe then—but cost you connection now.

In The Happiness Hypothesis, Jonathan Haidt points to a disturbing moment in psychological history that disrupted the natural development of secure attachment: the rise of behaviorism in the early 20th century.

John B. Watson, a founding figure of behaviorism, famously applied the same rigid, mechanistic principles he used on rats to raising human children. In his 1928 bestseller The Psychological Care of Infant and Child, he urged parents not to kiss their children, not to comfort them when they cried, and to withhold affection—believing emotional bonding would produce weak, dependent adults.

By the mid-20th century, attachment theory began to challenge these behaviorist claims. John Bowlby, in the 1950s, argued that infants form emotional bonds with caregivers as an innate survival mechanism—not merely as conditioned responses to rewards, as behaviorism suggested. His work, drawing from ethology, psychoanalysis, and control systems theory, moved beyond behaviorism’s narrow stimulus-response framework. Mary Ainsworth’s empirical research in the 1960s and ’70s, through her Strange Situation study, confirmed that attachment styles stem from caregiver sensitivity and infant security needs, rather than simple conditioning.

Yet, ironically, during the 1970s and ’80s, Christian parenting teachings—particularly those popularized by figures like Dobson—adopted and amplified the very behaviorist ideas that attachment research was already disproving. These teachings emphasized strict discipline and emotional control, often citing Scripture to justify practices rooted in outdated psychological theories rather than theology.

Let that sink in.

For decades, dominant parenting advice discouraged emotional responsiveness, treating affection not as a necessity but as a liability.

This wasn’t just bad advice—it was the psychological equivalent of nutritional starvation. Instead of missing vitamins, children missed attunement, safety, and connection. As attachment research has since shown, those early emotional experiences shape nervous system development, stress regulation, and whether someone grows up trusting or fearing closeness.

So, when we talk about stress responses like fawning… or chronic over-functioning… or emotional dysregulation… we're often seeing the adult expression of a nervous system that never learned what safety feels like in the presence of other people.

And that’s why today’s conversation matters. Because healing isn’t just about rewiring thought patterns. It’s about rebuilding your felt sense of safety—in your body, in your relationships, and in your life.

And if you are anything like me and have found yourself wondering… why your nervous system reacts the way it does… or why regulating your emotions feels impossible even when you “know better” … this episode will connect the dots in ways that are both validating and eye-opening.

We’re talking trauma, identity, neuroplasticity, stress, survival, and what it really means to come home to yourself.

The topics we explore:

The critical differences between PTSD and Complex PTSD — and how each impacts the brain and body

Why CPTSD isn’t just a fear response, but a full-body survival adaptation that reshapes your identity

What it means to heal “from the bottom up,” and why insight alone isn’t enough

How books and language can validate our experience — without replacing the need for somatic work

The push-pull of relational safety: why CPTSD makes connection feel risky, even when we crave it

How trauma affects the Default Mode Network, and why healing often feels like rediscovering who you are

Whether you’re navigating relational triggers, spiritual disorientation, or the long road of recovery, this conversation offers clarity, compassion, and a grounded path forward.

Please enjoy the interview!

LINKS:

Check out Cody’s work! About - The Mind, Brain, Body Digest

The Top 5 Childhood Core Wounds in Overachievers 🧠

No Bad Parts | IFS Institute | Schwartz

Transcending Trauma Healing Complex PTSD with Internal Family Systems Therapy

Share this post